Prisoner's Hall

In the 19th century, it was used as an exhibition gallery for ancient works gathered from various collections and ended at the Tribune where Michelangelo's sculptures were able to find accommodation, resulting in a unified route that terminates at the center of the Tribune where David is placed under a dome that takes the form of a halo.

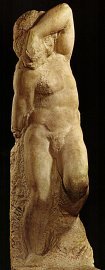

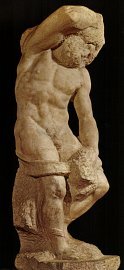

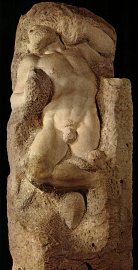

The name of the Hall takes its name from these four striking sculptures of male nudes, often referred to as the Slaves, Prisoners, or Captives. The works were started by Michelangelo himself for an immense tomb project for Pope Julius II della Rovere. The original commission dates back to 1505, before he was assigned the Sistine Chapel in 1508; it was intended to be the grandest tomb in Christian history, with over 40 figures. The four Prisoners were actually intended for pilasters on the lower level of a massive free-standing tomb designed for the center of old St Peter's Basilica in Rome.

It took Michelangelo several months for this particular task to seek out the marble of superior quality within the Carrara quarries; he personally chosen each block that he considered worthy and marked them with three circles. In the year 1506, however, he ceased to work on it because Pope Julius more and more did not have enough money to complete payment for this great work which also distracted him from other works like rebuilding Rome!

After the pope died in 1513, the first design was made smaller to less grand proportions with further changes in 1521 and then again in 1534 when it was decided to take the Prisoners out of the project and send them back to Florence.

Now after almost 40 long and stormy years later, the “tragedy of the sepulcher” came to an end. It was during this time that Michelangelo created some of his most famous sculptures for Julius II's tomb, among them the Moses (circa 1515) and now much reduced funerary monument, which today stands in a little-known St. Peter’s church in Rome—San Pietro in Vincoli. Michelangelo had in mind a tomb where the chamber would be painted with figures from both the Old and New Testaments, along with allegorical representations of the Arts and the Virtues prevailing over the Vices. According to him, his "Prisoners" signified the Soul bound within the Flesh, enslaved by human frailties.

At the artist's death, four of the Prisoners were found in his studio, and his nephew presented them to Duke Cosimo I de' Medici together with the Victory now in Palazzo Vecchio. The grotto was flanked in 1586 by Bernardo Buontalenti with sculptures at the corners of Boboli expansive Anunciacion Grotto set huge Gardens actor), Palazzo Pitti as (background located Vincenzo human-like In walls are artificial stalactites and stalagmites Resto it shows adorning stones and sponges sea-shell arrangement before man-made figure fossils prison where echoezon human grotto components were parts of Michelangelo's design. The Slaves remained in until 1908 when it was transferred to Galleria dell'Accademia.

Michelangelo's Prisoners

Of great repute are four statues in particular—known to scholars as "The Awakening Slave," "The Young Slave," "The Bearded Slave" and "The Atlas (or Bound)" because of their incomplete state. They are typical of Michelangelo's working technique called non-finito and, at the same time, stunning examples of conveying the idea of difficulties that beset an artist while extracting a figure from a block of marble, as well as mankind's aspiration to free a spirit from physical limitations.

There have been many different readings of these statues. One feels, at different stages in completion, the force with which creative ideas struggle toward liberty from the material weight and confinement surrounding them. They were possibly deliberately left incomplete by the artist to give expression to this universal condition whereby individuals strive to liberate themselves from their material constraints.

In viewing the Prisoners from several angles, Michelangelo’s deep feeling for and understanding of anatomy are revealed. While the heads and faces are among the least finished parts of these busts, they contribute very well to their basic meaning through their posture—classically in contrapposto. The Slaves place most of their weight on one foot so that this action causes the shoulders to slant against the hips and legs while, in turn, throwing one side of the body into marked disagreement with the other side. Movement is thus skillfully given to these carefully unbalanced figures as well as emotion; they also acquire a more dynamic, commanding presence as Prisoners due to this treatment by the artist.

Meet the Prisoners at Accademia Gallery

Michelangelo's "non-finito" (unfinished)

The Accademia's unfinished sculptures by Michelangelo are an apt example clarifying his philosophy and technique of carving. According to him, a sculptor was only an instrument of God. Therefore, his role was not to create but to uncover the powerful forms within the marble. The material surrounding the figure is what Michelangelo needed to cut away. His work was merely cutting into the rock around those shapes so that they were brought out properly.

Vasari writes that he never took off his boots for days at a time, and used the same clothing while at work in order not only of efficiency but also of skill and experience since if one knows what he is about it is easy enough to keep clean white marble free from dust (and impracticably cold in winter).

Indeed, preliminary phases are distinguishable because remnants left by mallet and pointed chisel show clearly on marble surfaces from this period when shape began emerging; Michelangelo started back-to-front while working freestyle on figures unlike other sculptors who drew outlines on their blocks after making plaster models. Having no truck with plaster models (nor even drawing on paper), Michelangelo began right with raw marble—freely conceived in three dimensions all at once—attacking masses most heavily before going into details toward completion, always gaining anatomy progressively just as much as form overall so that every part reveals workmanship being executed freshly till last touch put down assuredly.

As Vasari described in his "Lives of the Artists," these figures appeared to stand up from the marble "as if a form were rising to the surface of water." His method was to put a wax figure into a vessel of water and then gradually to expose it, so that he might discern those parts which were projecting farthest. He worked in the same way, for himself extracting first those parts of highest relief.

Michelangelo's St. Matthew

In 1503, Michelangelo obtained a commission to make statues of the twelve Apostles for the Florence Cathedral. His work on only one piece, St. Matthew, however got started. He was called to Rome by Julius II soon after he began working on it, so that it became his first sculpture left unfinished.

After the contract for the twelve Apostles' statues was annulled on 18 December 1505, Michelangelo in all likelihood resumed his work on St. Matthew the following year. Several references in letters of that period and a stylistic feature typical of this phase allow us to make such a hypothesis: the torsion of the head of the saint in contrast to the position of the chest, which seems inspired by the Hellenistic group Laocoön and His Sons (unearthed in 1506) which Michelangelo came to appreciate during that same year.

The inscription on the base tells us how it was in 1831 that the statue was moved from the courtyard of the Opera del Duomo di Firenze to the placement in front of the Atrium of the Accademia di Belle Arti. Later, in 1909, it would shift next door to this gallery building, as did the Prisoners in that same year.