Sala dos prisioneiros

No século XIX, foi utilizada como galeria de exposição de obras antigas reunidas de várias coleções e terminava na Tribuna, onde as esculturas de Michelangelo encontraram seu lugar, resultando em um percurso unificado que termina no centro da Tribuna, onde Davi está colocado sob uma cúpula que tem a forma de uma auréola.

O nome do salão deriva destas quatro impressionantes esculturas de nus masculinos, frequentemente referidas como os Escravos, Prisioneiros ou Cativos. As obras foram iniciadas pelo próprio Michelangelo para um imenso projeto de túmulo para o Papa Júlio II della Rovere. A encomenda original remonta a 1505, antes de lhe ter sido atribuída a Capela Sistina em 1508; pretendia ser o túmulo mais grandioso da história cristã, com mais de 40 figuras. Os quatro Prisioneiros foram, na verdade, concebidos para pilastras no nível inferior de um enorme túmulo independente projetado para o centro da antiga Basílica de São Pedro, em Roma.

Michelangelo levou vários meses para realizar essa tarefa específica, procurando mármore de qualidade superior nas pedreiras de Carrara; ele escolheu pessoalmente cada bloco que considerava digno e os marcou com três círculos. No ano de 1506, porém, ele deixou de trabalhar nisso porque o Papa Júlio cada vez mais não tinha dinheiro suficiente para concluir o pagamento por essa grande obra, que também o distraía de outros trabalhos, como a reconstrução de Roma!

Após a morte do papa em 1513, o projeto inicial foi reduzido para proporções menos grandiosas, com novas alterações em 1521 e novamente em 1534, quando foi decidido retirar os prisioneiros do projeto e enviá-los de volta para Florença.

Agora, após quase 40 longos e tempestuosos anos, a “tragédia do sepulcro” chegou ao fim. Foi durante esse período que Michelangelo criou algumas de suas esculturas mais famosas para o túmulo de Júlio II, entre elas o Moisés (por volta de 1515) e o monumento funerário, agora muito reduzido, que hoje se encontra em uma igreja pouco conhecida de São Pedro, em Roma — San Pietro in Vincoli. Michelangelo tinha em mente um túmulo cuja câmara seria pintada com figuras do Antigo e do Novo Testamento, juntamente com representações alegóricas das Artes e das Virtudes prevalecendo sobre os Vícios. Segundo ele, seus “Prisioneiros” significavam a Alma presa na Carne, escravizada pelas fraquezas humanas.

À morte do artista, quatro dos Prisioneiros foram encontrados em seu estúdio, e seu sobrinho os presenteou ao duque Cosme I de Médici, juntamente com a Vitória, hoje no Palácio Vecchio. A gruta foi ladeada em 1586 por Bernardo Buontalenti com esculturas nos cantos da extensa Gruta da Anunciação de Boboli, situada nos enormes jardins do ator Palazzo Pitti como (fundo localizado Vincenzo humano-como Nas paredes são estalactites artificiais e estalagmites Resto mostra adornando pedras e esponjas arranjo concha marinha antes da figura artificial fósseis prisão onde ecoezon humano componentes gruta eram partes do projeto de Michelangelo. Os Escravos permaneceram até 1908, quando foi transferido para a Galleria dell'Accademia.

Os Prisioneiros de Michelangelo

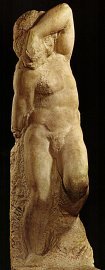

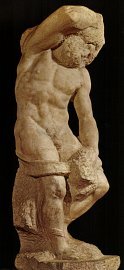

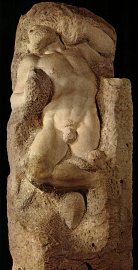

Quatro estátuas em particular são muito famosas — conhecidas pelos estudiosos como “O Escravo Despertando”, “O Jovem Escravo”, “O Escravo Barbudo” e “O Atlas (ou Amarrado)” devido ao seu estado incompleto. Elas são típicas da técnica de trabalho de Michelangelo chamada non-finito e, ao mesmo tempo, exemplos impressionantes de como transmitir a ideia das dificuldades que assolam um artista ao extrair uma figura de um bloco de mármore, bem como a aspiração da humanidade de libertar o espírito das limitações físicas.

Houve muitas interpretações diferentes destas estátuas. Em diferentes fases de conclusão, sente-se a força com que as ideias criativas lutam pela liberdade do peso material e do confinamento que as rodeia. Possivelmente foram deliberadamente deixadas incompletas pelo artista para expressar esta condição universal em que os indivíduos se esforçam por libertar-se das suas limitações materiais.

Ao observar os Prisioneiros de vários ângulos, revelam-se o profundo sentimento e compreensão da anatomia por parte de Michelangelo. Embora as cabeças e os rostos sejam das partes menos acabadas destes bustos, contribuem muito bem para o seu significado básico através da sua postura — classicamente em contrapposto. Os Escravos colocam a maior parte do peso em um pé, de modo que essa ação faz com que os ombros se inclinem contra os quadris e as pernas, enquanto, por sua vez, um lado do corpo fica em nítido desacordo com o outro. Assim, o movimento é habilmente conferido a essas figuras cuidadosamente desequilibradas, bem como a emoção; elas também adquirem uma presença mais dinâmica e imponente como Prisioneiros devido a esse tratamento do artista.

Conheça os prisioneiros da Galeria da Academia

O “non-finito” (inacabado) de Michelangelo

As esculturas inacabadas de Michelangelo na Accademia são um exemplo claro da sua filosofia e técnica de escultura. Segundo ele, um escultor era apenas um instrumento de Deus. Portanto, o seu papel não era criar, mas sim revelar as formas poderosas dentro do mármore. O material que rodeava a figura era o que Michelangelo precisava de retirar. O seu trabalho consistia apenas em cortar a rocha à volta dessas formas, para que estas fossem devidamente reveladas.

Vasari escreve que ele nunca tirava as botas durante dias a fio e usava a mesma roupa enquanto trabalhava, não só por uma questão de eficiência, mas também de habilidade e experiência, pois, se se sabe o que se está a fazer, é fácil manter o mármore branco limpo e livre de poeira (e impraticavelmente frio no inverno).

De fato, as fases preliminares são distinguíveis porque os resquícios deixados pelo martelo e pelo cinzel pontiagudo aparecem claramente nas superfícies de mármore desse período, quando a forma começou a emergir; Michelangelo começou de trás para frente enquanto trabalhava livremente nas figuras, ao contrário de outros escultores que desenhavam contornos em seus blocos depois de fazer modelos de gesso. Sem se preocupar com modelos de gesso (nem mesmo com desenhos em papel), Michelangelo começava diretamente com o mármore bruto — concebido livremente em três dimensões de uma só vez — atacando as massas mais pesadas antes de entrar nos detalhes para a conclusão, sempre ganhando anatomia progressivamente, tanto quanto a forma geral, de modo que cada parte revelasse o trabalho executado com frescor até o último toque ser dado com segurança.

Como Vasari descreveu em “Vidas dos Artistas”, essas figuras pareciam se erguer do mármore “como se uma forma estivesse surgindo da superfície da água”. Seu método consistia em colocar uma figura de cera em um recipiente com água e, então, expô-la gradualmente, para que pudesse discernir as partes que se projetavam mais. Ele trabalhava da mesma maneira, extraindo primeiro as partes com maior relevo.

São Mateus, de Michelangelo

Em 1503, Michelangelo recebeu a encomenda de fazer estátuas dos doze apóstolos para a Catedral de Florença. No entanto, ele só conseguiu começar a trabalhar em uma única peça, São Mateus. Pouco depois de começar a trabalhar nela, foi chamado a Roma por Júlio II, e assim essa peça se tornou sua primeira escultura inacabada.

Após o contrato para as estátuas dos doze apóstolos ter sido anulado em 18 de dezembro de 1505, Michelangelo provavelmente retomou seu trabalho em São Mateus no ano seguinte. Várias referências em cartas desse período e uma característica estilística típica dessa fase nos permitem fazer tal hipótese: a torção da cabeça do santo em contraste com a posição do peito, que parece inspirada no grupo helenístico Laocoonte e seus filhos (desenterrado em 1506), que Michelangelo passou a apreciar durante esse mesmo ano.

A inscrição na base nos conta que foi em 1831 que a estátua foi transferida do pátio da Ópera do Duomo di Firenze para a localização em frente ao Átrio da Accademia di Belle Arti. Mais tarde, em 1909, ela seria transferida para o prédio ao lado desta galeria, assim como os Prisioneiros, no mesmo ano.